Bottleneck is a series of visual narratives that provoke an examination of our relationship to plastic bottles. The main actor in Bottleneck is the ordinary plastic beverage bottle– polyethylene terephthalate (PET) which I altered into different shapes. This series commemorates the 50 year anniversary that has bonded people, PET plastic, and the planet.

The main problem is not plastic, it's how we use it.

It’s a marvel of modern engineering that every second, we are able to produce 20,000 new bottles globally. Fortunately, they are made from polymers that can be collected, processed, and remade into new products. But the rate of production is so efficient that it far exceeds our ability and infrastructure to collect and process it.

The perceived value of plastic is that it’s cheap, disposable, and recyclable. While Americans consumed 50 billion plastic water bottles in 2013, a whopping 38 billion never made it to recycling centers. That means that over than 3/4 of all bottles end up in landfill or the oceans where they will never separate into basic elements– carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, chlorine, and sulfur.

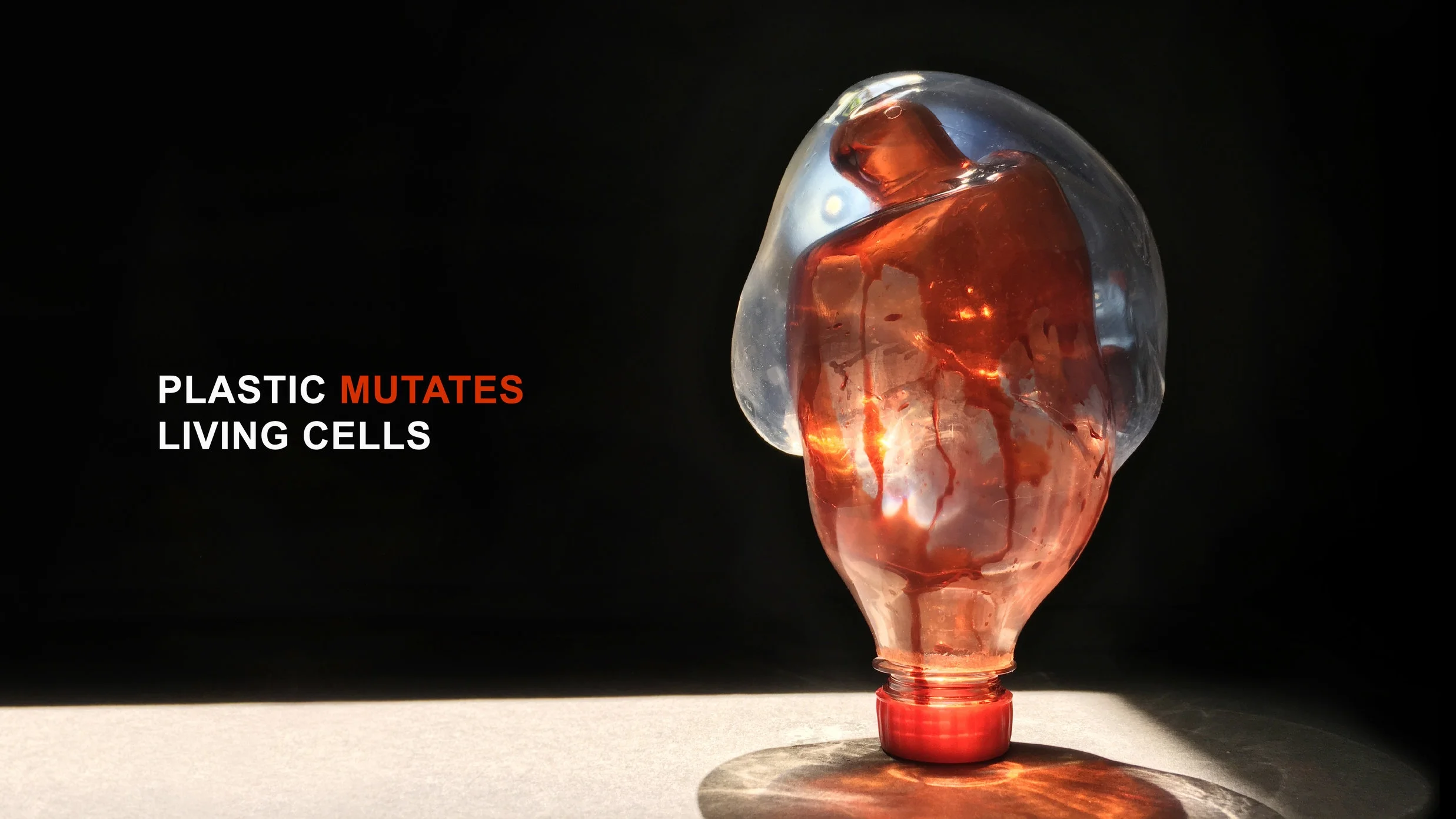

This beautiful material is so unforgivably durable, it’s a permanent fixture in our ecosystem. Discarded plastic will continually break down into smaller and smaller pieces– until it is so minuscule, that we can drink it without noticing. The smallest of micro-plastic particles pass through the filters that we use to purify our drinking water. What a journey– from our refrigerator to the ocean and back into our kidneys, liver, and internal organs. Quite simply, plastic is forever.

We are literally eating and drinking microplastic.

Every second, humans produce 20,000 new plastic bottles globally.

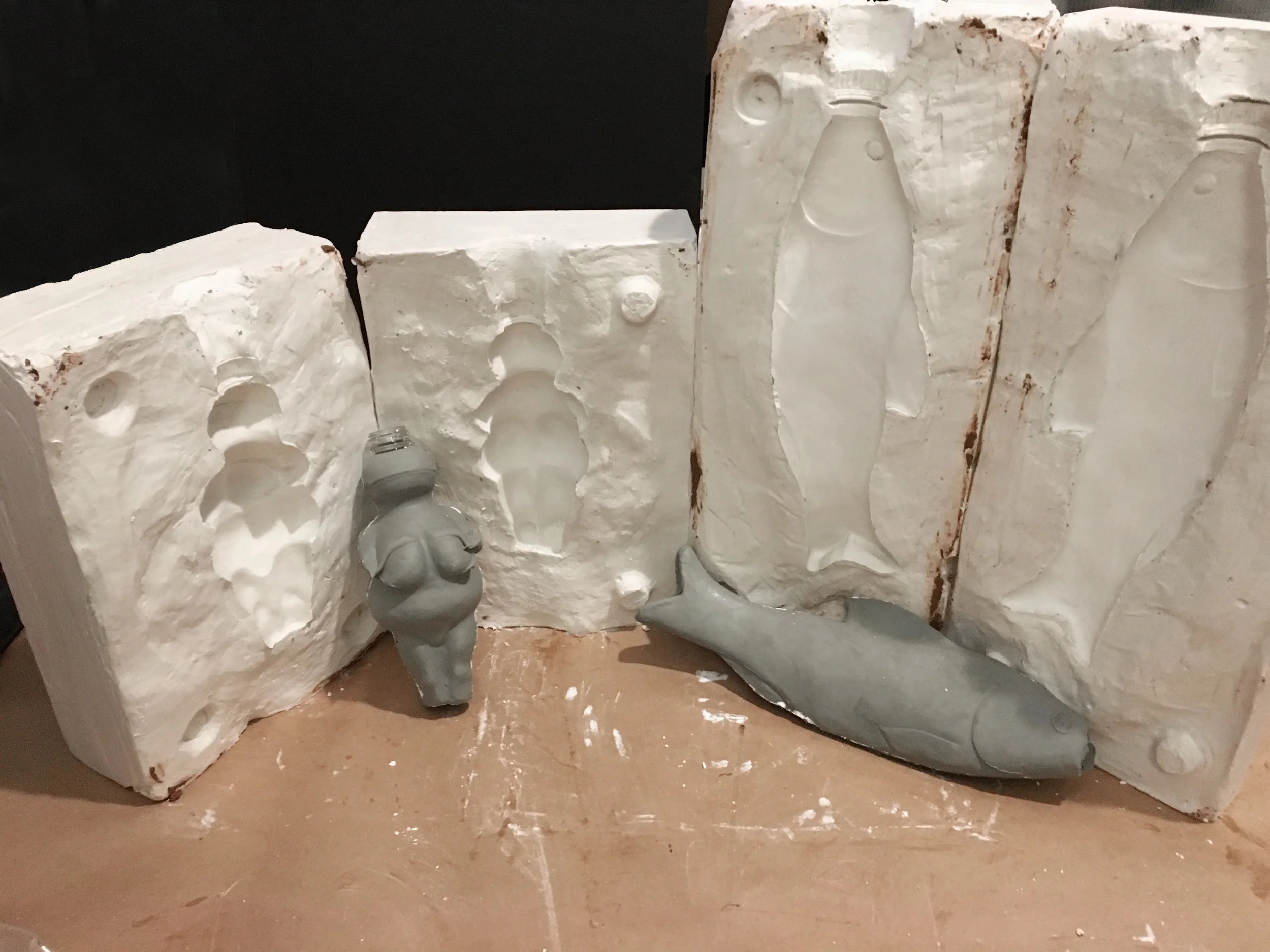

THE Venus BOTTLE

VENUS OF WILLENDORF– a figurative sculpture from the Upper Paleolithic Period some 23,000 years ago. Traditionally referred to in archeology as the “Venus figurines,” this has become a symbol of mother goddess: a personification of nature, motherhood, fertility, or one who embodies the bounty of the earth.

The Venus bottle signifies the problem with estrogenic activity (EA) caused by endocrine disrupter’s, found in nearly all plastics. Chronic diseases, including cancer, impaired immune function, early onset of puberty, obesity, diabetes, and hyperactivity, have been linked to low doses of the chemical Bisphenol A (BPA). In addition to hundreds of peer-reviewed studies, scientists at CertiChem, PlastiPure, Georgetown University, and the University of Texas published a paper on EA in plastic materials and commercial products. Published in 2011, it appeared in the peer-reviewed journal, Environmental Health Perspectives. The results of this study indicate that a large majority of commercially available BPA-free plastic materials and other plastic products readily leach chemicals that cause EA. Leaching increases when products are subjected to common-use stresses, such as dish washing, microwaving, and sunlight. The study also found that plastic pellets may not contain EA disrupting chemicals, but the proprietary additives used in the manufacturing the pellets into bottles are the source of disruption. In 2012, the FDA finally banned BPA plastic from baby bottles and sippy-cups nationwide, since developing infants and children are most at risk from this chemical, which mimics the hormone estrogen.

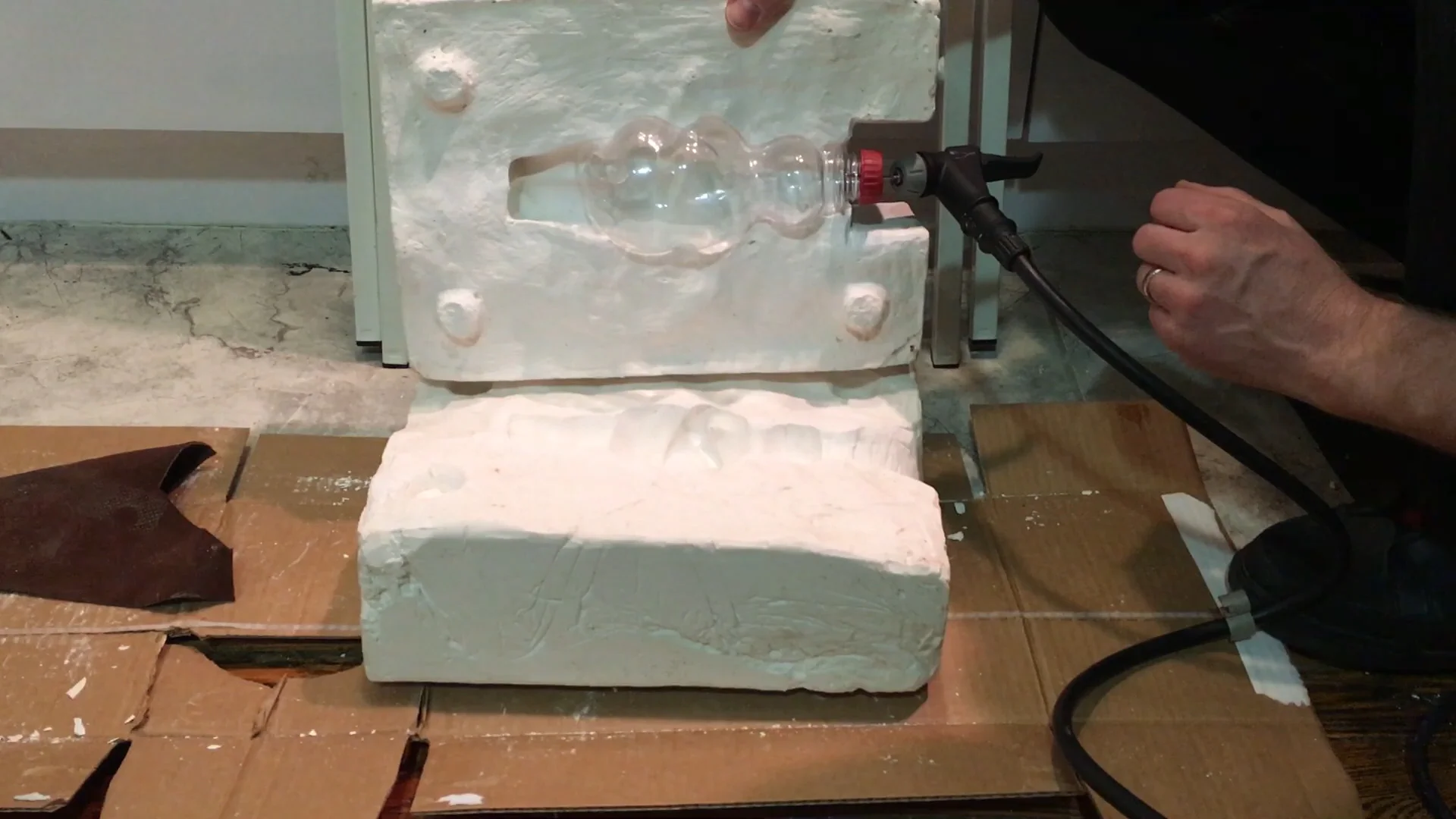

PROCESS

Using traditional techniques and oil clay, I sculpted the figure and cast plaster negative molds to produce these custom injection molded plastic bottles.

Since the mid 1970’s, the most widely used plastic for disposable beverage containers is polyethylene terephthalate (PET). On average, PET has an elasticity limit of 50 to 150 percent by volume, with a working temperature just below 200 degrees Fahrenheit. Injection molds are used to form PET and produce consistent, engineered results in mass quantity, very rapidly.

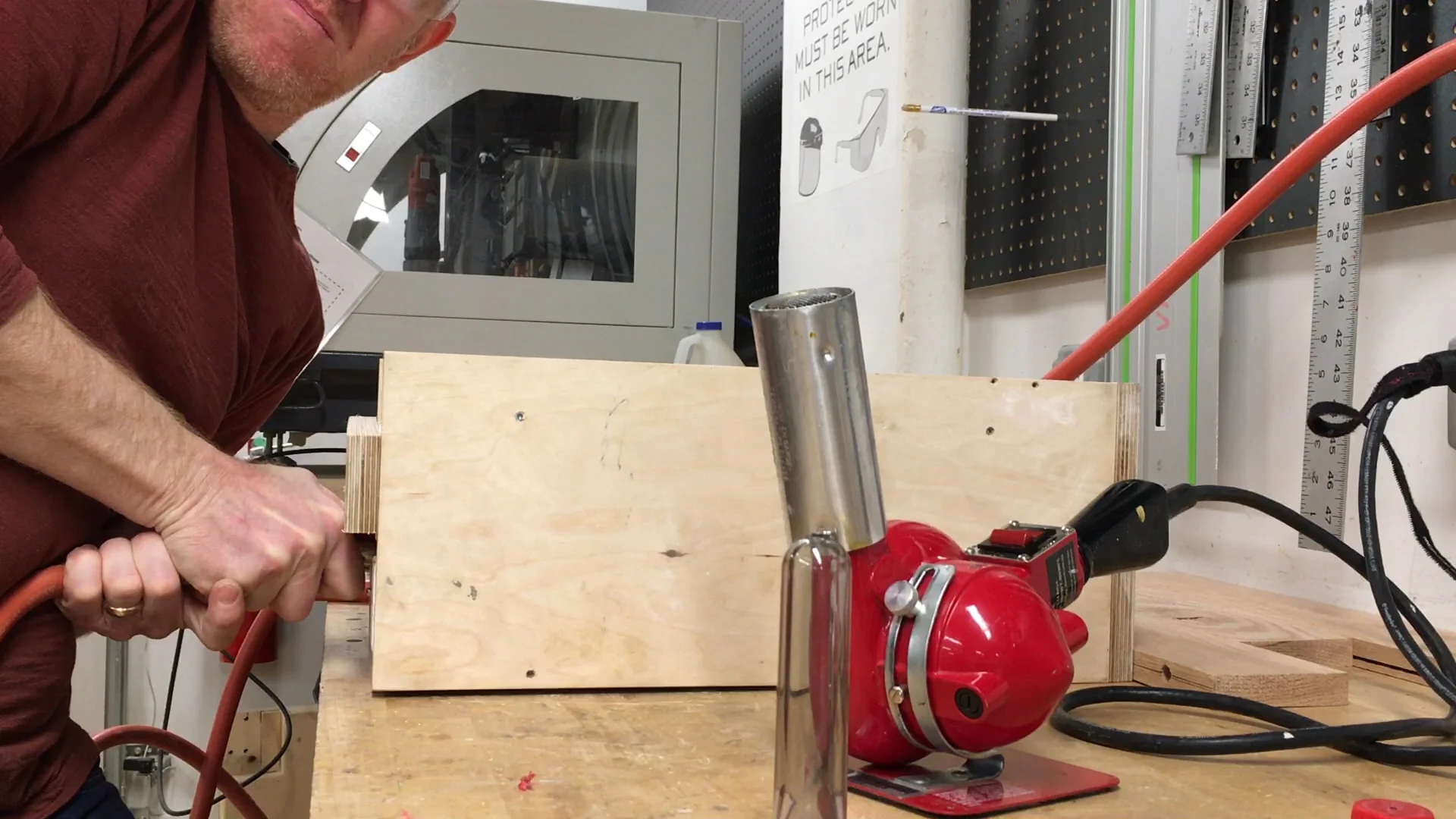

I learned to work polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic with and without molds in a process known as free-form (glassblowing is a direct parallel to this method). Began by routinely collecting discarded bottles from the curbside, I manipulating them using a heat gun, bicycle pump, and water. Experimentation was the key to provide insights into the behavior, properties, and tolerances of PET. Applying heat to a bottle will shrink it, while heating and pressurizing causes expansion. Similar to working hot metal, water is used to isolate the heat and direct where the change in shape will occur.

Many of my bottles began with a test tube-like plastic shape called a “preform.” Each preform is heated to 180 degrees F before inserting into the mold, clamping, and pressurizing it.